Seasonality of biofouling on ships

Biofouling – the accumulation of marine organisms on ship hulls – varies significantly with seasonal and regional conditions. Peer-reviewed studies show that both the intensity of fouling and the composition of fouling communities change with seasons. Below, we summarize how seasonal patterns manifest in different climates and regions, and what scientific research has found about these natural biofouling processes on ships.

In this article we discuss:

Seasonal variation in biofouling intensity

Temperature is a key driver of fouling growth rates and explains much of the seasonal variation. In cold polar waters (≈<5 °C), biofouling is minimal and generally limited to the brief summer months when water warms enough for organisms to grow. By contrast, tropical waters (>20 °C) provide favourable conditions year-round. Fouling in warm tropical seas is continuous and intense, since many fouling organisms can reproduce and grow throughout the year without a true dormant season. Temperate regions (mid-latitudes, ~5–20 °C) fall in between: fouling occurs year-round but shows strong seasonality, with the most rapid growth and heavy settlement happening in the warm spring and summer months, and a slowdown during colder fall/winter periods.

In temperate ports, it’s common to see fouling flourish in late spring and summer (when larvae and spores are most abundant) and then diminish in the cooler winter.

Examples from the field

Field studies confirm these trends. For instance, an EPA survey notes that marine growth on ships “flourishes during warmer months and diminishes in cooler months,” linked to peaks in reproductive propagules in spring/summer.

In a tropical monsoon climate like the Indian coast, researchers observed striking seasonal differences in fouling accumulation: on test panels in the Gulf of Mannar (India), biomass buildup reached as high as ~1.38 kg per panel during the warm southwest monsoon (summer) season, whereas during the cooler northeast monsoon (winter) season the fouling biomass was much lower due to reduced larval settlement. This aligns with the idea that warmer, nutrient-rich seasons drive more intense fouling. Even in subtropical enclosed seas, heat plays a role – e.g. in the Arabian Gulf, 6-month immersion tests found that panels in Oman’s warm coastal waters accumulated nearly three times the fouling biomass of those in cooler, more saline Kuwaiti waters over the same period. Such data from the field shows that higher temperatures and favorable conditions in certain seasons dramatically increase fouling intensity.

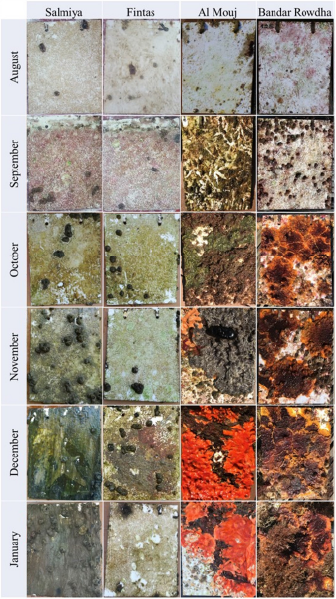

the sampling locations in Kuwait (Fintas and Salmiya) and Oman (Bandar

Rowdha and Al Mouj) during the sampling period of 6 months from August

2017 to January 2018. Image credits: Frontiers in Marine Science

Seasonal shifts in fouling community composition

Biofouling community make-up is strongly influenced by seasonal cycles. Different fouling organisms have distinct reproductive timing and growth periods, leading to seasonal succession on immersed surfaces:

Barnacles and other macrofouling

Many hard-fouling animals breed or recruit seasonally. For example, a long-term study in tropical India showed that the barnacle Amphibalanus amphitrite (a common hull-fouling barnacle) was present and breeding year-round, whereas another barnacle species A. variegatus settled only during winter months (northeast monsoon). That is, one species maintained continuous presence, while the other had a distinct seasonal window.

Similarly, researchers have noted that recruitment of common hull-fouling invertebrates like barnacles, bivalve mollusks, and bryozoans can peak in different seasons depending on the species. In the Indian study, a pearl oyster (Pinctada sp.) was found to settle primarily in late spring–summer, contributing substantially to fouling biomass in those months.

By contrast, barnacles became especially dominant after the monsoon, when competition from other species was lower. These shifts show that the fouling community on a ship can look very different in summer (e.g. more bivalves and algal growth) than in winter (when cold-tolerant barnacles or bryozoans might dominate).

Microfouling and algal films

Seasonal patterns also extend to the early-stage biofilm organisms. Diatom films and microbial biofouling exhibit seasonal succession which can influence later macrofouling. A study on fouling diatom communities on the Yantai coast of China (temperate zone) found the lowest diatom densities in winter, while summer and autumn samples showed the highest species richness and diversity of diatoms.

This means the composition of the slimy biofilm on a hull in winter (often sparse and less diverse) will differ from that in summer (thicker, more diverse, and potentially harboring larvae of macrofouling organisms). These microfouling changes can set the stage for which macro-organisms successfully settle later each season.

In short, the ecology of hull fouling communities is dynamic over time: many organisms have seasonal life cycles, so the dominant fouling species on a ship can rotate through the year. Understanding these natural cycles is important, as knowledge of when certain high-impact species (e.g. barnacles or tubeworms) tend to settle can inform timing of hull inspections or cleaning.

Geographic and regional differences in seasonality

Seasonal biofouling patterns can be more or less pronounced depending on the region where a ship operates. Coastal and offshore environments differ in how much fouling pressure they exert, and certain regions are known “hotspots” for fouling due to climate and productivity:

Tropical coastal waters

Warm coastal regions in the tropics (e.g. Southeast Asia, Indian Ocean, Caribbean) are among the most affected by heavy biofouling. Because water temperatures remain high year-round, these areas support continuous reproduction of fouling organisms. Fouling communities in tropical ports can develop very rapidly at any time of year. For example, in the Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea regions, researchers report rapid accumulation of barnacles, mussels, algae, and tubeworms on ships, with only slight lulls during any “cool” season. Tropical coastal waters thus tend to produce thick, diverse fouling on ships unless very frequent cleaning is done.

Temperate regions

Coastal waters in temperate zones (e.g. North Atlantic, Mediterranean, Northeast Asia) experience strong seasonal swings in fouling. These areas still produce significant hull growths but mostly concentrated in the late spring to early fall period. During summer, temperate ports see blooms of fouling larvae (barnacle spatfalls, algal spores, etc.), often leading to a surge of hull fouling if ships remain idle. In winter, cold temperatures slow metabolism and reproduction of fouling organisms, so ships in cold temperate waters tend to accumulate much less new growth.

Field example

Studies in European harbors note that ships gather most of their yearly fouling during the warm months, while winter lay-up results in relatively little new growth. Nonetheless, temperate coastal regions can have very high fouling intensity in peak season – comparable to the tropics for a few months – with common fouling pecies being barnacles, mussels, seaweeds, and bryozoans.

Polar and subpolar waters

High-latitude seas (Arctic, sub-Arctic, and Antarctic regions) are the least conducive to biofouling. Low water temperatures and ice cover restrict the growing season. Fouling in these regions is largely confined to the short summer window when water temperatures rise enough for larvae to develop. Even then, polar fouling communities are relatively sparse and slow-growing (often dominated by cold-water barnacles or bryozoans).

Ships operating in polar waters generally experience minimal biofouling, and any organisms that do attach often stop growing or die off in winter when temperatures drop near freezing.

That said, if a vessel from temperate/tropical ports enters polar regions, some hardy fouling species can survive for a time in colder water, but overall polar regions are less affected by fouling pressure compared to lower latitudes.

Offshore (open ocean) vs. coastal waters

Proximity to shore strongly influences fouling rates.

Coastal waters, especially near estuaries and productive continental shelf areas, are rich in plankton and larval stages of fouling organisms, leading to higher colonization pressure on ships in port or nearshore. By contrast, the open ocean has fewer benthic larvae in the water column (far from coastal breeding grounds), so ships on long offshore voyages tend to accumulate fouling more slowly.

Additionally, vessels moving at speed in open water create flow conditions that make it hard for larvae to attach. Research confirms that a substratum closer to shore has a higher probability of successful fouling settlement due to greater larval supply.

For example, static platform structures near coasts foul quickly, whereas instruments deployed in the open ocean often stay cleaner for longer. In the context of ships, a recent study compared a coastal-operating vessel to an open-ocean vessel and found the coastal ship’s hull harbored a much richer fouling community than the ocean-going ship.

The deep-sea research vessels in that study spent very little time anchored in port (only a few days per year), giving fouling organisms few opportunities to settle on their hulls. In contrast, vessels that linger in port or coastal waters for extended periods quickly accumulate diverse fouling growth. In short, ships active in coastal regions (or sitting idle) are most affected by intense biofouling, whereas those that transit continuously offshore and rarely stop have lower fouling loads.

Key takeaways

Seasonal peaks

Peer-reviewed literature over the past decade consistently shows fouling peaks in the warm season. From the Arabian Gulf to the North Atlantic, ships experience the highest biofouling intensity during periods of higher water temperature (spring/summer). Cooler seasons see reduced fouling growth.

Seasonal community changes

The types of organisms fouling a ship’s hull can shift with the seasons. Many temperate and tropical area studies document a succession of species: early-season films of bacteria and diatoms give way to barnacle and tubeworm recruitment, followed by later colonizers like mussels or tunicates, depending on the time of year. Knowing these patterns can help predict fouling outbreaks (e.g. barnacle “settlement season”).

Regional hotspots

Warm, coastal regions (e.g. Southeast Asia, Pacific Islands, the Indian Ocean coastlines) are most prone to heavy year-round fouling, whereas cold regions (open ocean, high latitudes) are less so. Tropical harbors can foul a ship in a matter of weeks, while a ship crossing the open Pacific may accumulate relatively little new growth in transit.

Overall, seasonality plays a crucial role in marine biofouling on ships. Studies all reinforce the idea that “when” and “where” a ship operates will strongly influence how much and what kind of fouling it incurs. Warmer seasons and productive coastal waters drive the highest fouling risk, while colder periods and open-ocean operations can provide a partial reprieve. Understanding these natural fouling cycles is important for timing maintenance and mitigating biofouling impacts on shipping operations.

Year‑round biofouling protection with Cathelco systems

Cathelco’s ultrasonic antifouling systems prevent early-stage biofilm on hulls and components, while marine growth prevention systems (MGPS) protect internal pipework from blockage by barnacles and mussels. Together, these solutions support continuous biofouling control, reduce fuel consumption, and help limit the spread of invasive species across seasons and regions.