A comprehensive list of Invasive Aquatic Species (IAS) threatening marine ecosystems

Did you know that Invasive Aquatic Species (IAS) are widely recognised as a major pressure on marine and coastal biodiversity. When non native organisms establish in a new environment, they can compete with local species, change habitats, and disrupt food webs. For ports, coastal authorities, and vessel operators, IAS also create operational and compliance risk.

In this guide, we explain what invasive aquatic species are and summarise practical steps to reduce the likelihood of transfer via ships.

What are Invasive Aquatic Species (IAS)?

InInvasive aquatic species are organisms introduced outside their natural range into an aquatic environment. They can include plants, animals, algae, and microorganisms. Not all non native species become invasive, but some establish successfully, spread quickly, and cause ecological or economic harm.

Common pathways that support spread include:

Human activity

Recreational boating, fishing, aquaculture activities, and movement of marine equipment can unintentionally transport organisms into new environments.

Ballast water from ships

Ships take on ballast water in one region and discharge it in another. That process can move a wide range of organisms between ports. This pathway has historically been a major contributor to marine introductions, and regulatory requirements and improved ballast water management practices have reduced risk in many parts of the industry.

Ship hulls and niche areas

A ship’s hull is the largest submerged surface and can transport attached marine growth between ports and regions. Risk is often concentrated in niche areas such as sea chests, gratings and strainers, rudders, and thruster tunnels. These recessed and complex spaces are harder to access, inspect, and clean, which makes them more prone to biofouling accumulation. Biofouling transfer is increasingly addressed through guidance and regional requirements, and further regulatory development is expected in coming years.

In addition, in water cleaning without capture or containment can release removed biofouling and coating debris into the sea. Uncontained discharge is recognised as a potential pathway for IAS spread.

Climate change

As seawater temperatures change, conditions that previously limited certain species can shift. Warmer temperatures can increase the likelihood that some non native organisms survive and establish in new regions.

Why marine environments are vulnerable to invasion?

Many marine habitats are diverse and productive, but they can also be sensitive to disturbance. Introducing a single invasive species can create knock on effects across multiple trophic levels, particularly when the newcomer is a strong competitor, an effective predator, or alters the physical habitat.

Common and well known Invasive Aquatic Species affecting marine ecosystems

Below are examples frequently referenced in discussions on marine and coastal invasions and shipping related transfer pathways.

Zebra mussels

Zebra mussels are native to freshwater systems in parts of eastern Europe and western Asia. They were introduced to North America in the 1980s through ballast water discharge and spread rapidly by attaching to boats and equipment moving between waterways. Zebra mussels filter large volumes of water, which can increase water clarity. At the same time, filtration can reduce phytoplankton availability for native species. They also form dense colonies and often outcompete native mussels and other bivalves for space and resources.

European green crab

European green crabs originate from the northeast Atlantic and have been introduced to new coastlines through shipping related transport, including ballast water. Once established, they can spread along coasts through natural movement and additional transport on vessels and marine equipment. They prey on native shellfish such as clams and oysters and compete with native crabs for food and habitat. Their burrowing behaviour can disturb sediments and damage eelgrass beds, which are important habitats for many coastal species.

Lionfish

Lionfish are native to the Indo Pacific and were introduced to the western Atlantic largely through the release or escape of aquarium kept species. After introduction, they spread rapidly as larvae disperse with ocean currents. Lionfish are effective predators that feed on a wide range of reef fish, which can reduce native fish populations and alter reef community composition.

Asian shore crab

Asian shore crabs were first recorded on the US east coast in the 1980s. Their introduction is commonly linked to shipping related pathways such as ballast water and stowaway transport on vessels or cargo. They can spread further through coastal movement and repeated transport between ports. Asian shore crabs compete with native crabs for food and shelter and can reach high densities in suitable habitats. They also prey on native molluscs, adding pressure to local shoreline ecosystems.

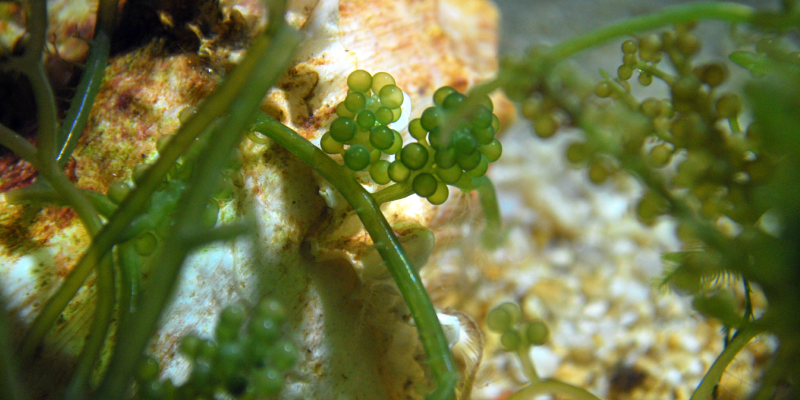

Caulerpa seaweed

Caulerpa species have spread outside their native range through the release or escape of aquarium kept organisms and through fragment transfer on anchors, fishing gear, diving equipment, and marine infrastructure. Because some Caulerpa can regrow from small fragments, even minor breakage can contribute to new outbreaks. Caulerpa can form dense mats that crowd out native seagrass and algae, reducing habitat quality for species that depend on those environments. Over time, this can change the structure of the seabed habitat and the communities that live there.

The impact of Invasive Aquatic Species

IAS introductions are not only a conservation issue. They can affect coastal infrastructure, fisheries, tourism, and vessel and port operations. Impacts vary by species and location, but the patterns below are common.

Competition with native species

Many invasive species compete directly with native organisms for food, space, and habitat. When an invasive species has fewer predators, higher reproduction rates, or broader environmental tolerance, it can gain a strong advantage.

European green crab is a widely cited example because it preys on shellfish and competes with native crabs. In areas where populations establish, local shellfish beds can be affected, with consequences for ecosystems and fisheries.

Research from the Journal of Fish Biology shows that competition can also destabilize local communities. As habitats degrade and resources become more limited, pressure increases across the food web. In some cases, less competitive species are displaced from key habitats, reducing overall biodiversity.

Habitat degradation

Some IAS alter the physical or chemical conditions of habitats, which can create long term changes in ecosystem structure.

Zebra mussels, for example, can alter aquatic systems by filtering phytoplankton, shifting nutrient pathways, and changing the conditions that support native fish and invertebrates. On reefs, invasive predators such as lionfish can reduce herbivorous fish populations that help control algal growth. That can indirectly contribute to reef degradation, especially where reefs are already stressed by global warming, pollution, and/or overfishing.

Economic impacts

The economic cost of IAS can be significant, particularly where invasive organisms affect fisheries, tourism, and infrastructure.

European green crab can threaten shellfish industries because commercially important species are part of its diet. Fouling organisms can also create operational problems. Zebra mussels are a well known example due to their ability to colonize and clog pipes and water intake systems on ships, increasing maintenance and cleaning requirements. Overall, invasive aquatic species damage is estimated at $120 billion annually in the US alone.

In shipping, biofouling that carries IAS increases drag and can reduce hydrodynamic performance, contributing to higher fuel consumption and emissions. For vessel operators, that creates a combined cost and compliance challenge.

Cascading impacts through marine food chains

IAS can disrupt established ecological relationships. Invasive predators may reduce prey populations directly and also compete with native predators for food. Over time, these changes can shift which species dominate an ecosystem and how energy moves through the food chain.

How to prevent the spread of Aquatic Invasive Species

Reducing IAS transfer risk requires a practical, multi-layer approach that combines operational controls with prevention technologies. The most effective programmes focus on stopping organisms from establishing in the first place and reducing the likelihood of release during maintenance activities.

Key prevention strategies

Manage biofouling in niche areas

Niche areas are often higher risk because they provide shelter from flow and are more difficult to inspect and clean. Marine growth prevention systems (MGPS) can help reduce fouling build up in seawater intakes and internal seawater systems. By using niche area mounted anodes to control conditions that support settlement and growth, MGPS can reduce the likelihood that organisms establish and are transported between regions.

Reduce hull biofouling to limit transfer risk

Ultrasonic antifouling systems use high frequency sound to create micro vibrations in the structure, which can make it harder for fouling to establish on treated surfaces. This approach can support hull cleanliness between maintenance windows and reduce drag build up over time.

Cathelco’s DragGone is an example of an ultrasonic antifouling system designed to support hull performance and efficiency. By helping to limit fouling accumulation, ultrasonic systems can also reduce reliance on frequent reactive cleaning and support broader biofouling management planning.

Use responsible in water cleaning practices

If in water cleaning is used, capture and containment can reduce the risk of releasing living organisms and coating debris into the surrounding environment. This is increasingly important for invasive species control and for local environmental requirements.

Control measures that support long term management

Biofouling management plans (BMP)

Many jurisdictions require ships to maintain a documented plan that outlines inspection routines, maintenance schedules, and cleaning procedures.

Biofouling record books

Keeping clear records of inspections, cleaning events, and actions taken helps demonstrate due diligence and supports operational consistency across voyages.

Protect your vessels from invasive aquatic species

Unchecked invasive aquatic species can disrupt ecosystems, affect fisheries, and increase operational costs in shipping. Prevention is most effective when it is proactive and practical, combining good housekeeping with technologies that reduce the likelihood of fouling establishment in the first place.

Cathelco supports operators with marine growth prevention systems for seawater intakes and internal seawater systems, and ultrasonic antifouling systems for hull performance support. If you would like to discuss biofouling risk reduction for your vessel type and trading profile, speak with our team.

Consult experts today to learn how Cathelco’s advanced technologies can help you deal with aquatic invasive species.